Celebrate the enduring legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. by finding hope through community. The MLK Holiday, observed annually on the third Monday of January, this year falls on January 20. Check the list below to find free and low-cost events to join with others across the state to reflect on, honor, and advance the legacy of Dr. King.

MLK Community Conference

When: January 16 · 9 a.m. – 2:30 p.m.

What: As part of the State of Minnesota’s “One Dream. One Minnesota” MLK celebrations, this second annual conference is brought to you in partnership with Metropolitan State University and features speakers and interactive workshops. There will also be a keynote address, an interactive workshop, and a panel discussion featuring networking and resource booths. Lunch will be provided. Admission is free, but capacity is limited.

Where: Metropolitan State University, 700 East 7th S., St. Paul

More info: https://bit.ly/4h4pR4Q

Sweet Potato Comfort Pie 10th Annual Martin Luther King Holiday of Service

When: January 19 · 1:30-4:30 p.m.

What: Sweet Potato Pie’s annual event returns for its 10th year to honor MLK’s legacy through service, sharing, and celebration. A preshow awards reception begins at 1:30 p.m. featuring the Character Values Photo Exhibit, the Upholding Our Beloved Community Awards, and featured musician Mari Harris. Following the pre-show, live music will be played by Jerome Richardson, Jamela Pettiford and the GQ unit, Shir Harmony, and others. Food and refreshments will be provided. This is a free event.

Where: Metropolitan Ballroom & Clubroom, 5418 Wayzata Blvd., Golden Valley

More info: https://bit.ly/40qaDla

44th Annual U of M Martin Luther King, Jr. Tribute Concert: Light

When: January 19 · 3 p.m.

What: With the theme of transforming light to darkness, G. Phillip Shoultz, III, and VocalEssence Singers of This Age, along with others, will perform a tribute to the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. This is a free event.

Where: Ted Mann Concert Hall, 2128 Fourth St. S., Minneapolis

More info: https://bit.ly/40no4Cu

MLK Community Worship Service

When: January 19 · 4 p.m.

What: The Duluth NAACP invites community members to this worship service to experience a modern-day expression of the Black Church tradition that nurtured the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Where: Peace United Church of Christ, 1111 North 11th Ave. E., Duluth

More info: www.duluthnaacp.org/mlk

St. Cloud State University MLK Community Celebration

When: January 20 · 8-10:30 a.m.

What: St. Cloud State University’s signature MLK Community Celebration will commence at 8 a.m. at the River’s Edge Convention Center. A community conversation will kick off the event, along with the announcement of the 2025 MLK Celebration Humanitarian Award, Dexter R. Stanton Essay, and Visual Art Contest winners, and a keynote address by Dr. Evelyn Hill. This is a free event.

Where: River’s Edge Convention Center, 10 Fourth Ave. S., St. Cloud

More info: https://bit.ly/40njnIG

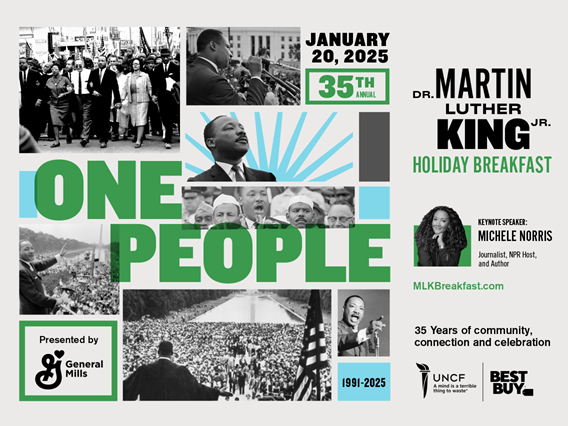

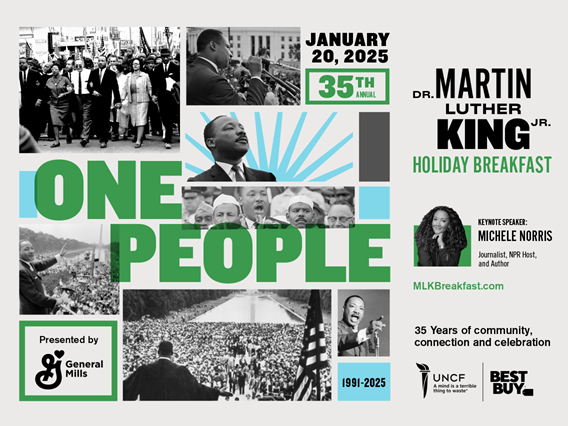

35th Annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Holiday Breakfast

When: January 20 · 8 – 9:30 a.m.

What: Under the theme “One People,” this annual event will honor the life and legacy of Dr. King while raising funds for students in the Twin Cities. This year’s keynote speaker is Michele Norris, senior contributing editor for MSNBC, former NPR host, and the author of “Our Hidden Conversations: What Americans Really Think About Race & Identity.”

The Sounds of Blackness will perform, and the Threads Dance Project and the VocalEssence Singers of This Age will offer special performances.

Where: Minneapolis Convention Center (Exhibit Hall A), 1301 Second Ave. S., Minneapolis

More info: MLKBreakfast.com. This breakfast will also be screened at many community locations.

39th Annual Martin Luther King, Jr. Day Celebration

When: January 20 · 10 a.m.

What: You are invited to advance Dr. King’s dream at the closing event for the State of Minnesota’s 39th Annual Martin Luther King Jr. Celebration, one of the oldest and largest celebrations in the nation.

With the theme of “One Dream. One Minnesota. Bridging Legacy with Action,” this closing event features community leaders and performances by Billy Steele and Fellowship Baptist Church, Jamecia Bennett, and Known MPLS. Dr. Yohuru Williams will MC and host a fireside chat by revered elders Josie R. Johnson and Reatha Clark King. To view the recorded live stream of the MLK, Jr. Celebration on January 20, 2025, visit TPT.org.

Where: Ordway Music Theater, 345 Washington St., St. Paul

More info: mn.gov/oeoa/events/2025-mlk-day.jsp

2025 MLK Day Service Project!

When: January 20 · 10 – 11:30 a.m.

What: This annual event offers an opportunity to honor Dr. King’s legacy by serving others. Make a difference on this powerful day by joining other community members in volunteerism at the Minneapolis Convention Center. This event is free but with limited capacity. Register at the link below.

Where: Minneapolis Convention Center, 1301 2nd Ave. S., Minneapolis

More info: https://bit.ly/4fQ3M8U

27th Annual Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Day Celebration

When: January 20 · 10 a.m. -1:30 p.m.

What: This MLK celebration features performing artists, community partners driving clear examples of equity forward work, a complimentary lunch, a fun-filled gift station for kids, and an overall experience founded on the principles upheld by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. This is a free event.

Where: Powderhorn Recreation Center, 3400 15th Ave. S., Minneapolis

More info: www.ppna.org/mlkcelebration

KMOJ’s 12th Annual Soul Bowl

When: January 20 · 10 a.m. – 4 p.m.

What: Celebrate the Martin Luther King holiday with other community members at KMOJ’s 12th Annual Soul Bowl.

More info: https://bit.ly/3BX44ND

Duluth NAACP MLK Gathering and March

When: January 20 · 10:30-11:45 a.m.

What: The Duluth NAACP will honor the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. with this annual march at the Family Freedom Center (Washington Center Gymnasium), starting at the entrance between 3rd and 4th Street on 1st Ave. West and begin on Lake St. between 3rd and 4th Avenue. A rally will follow at DECC-Symphony Hall, 350 Harbor Dr., Duluth, from 12-1:30 p.m.

More info: www.duluthnaacp.org/mlk

Mpls NAACP Martin Luther King Jr. Day Luncheon

When: January 20 · 11:30 a.m. – 2 p.m.

What: The Minneapolis NAACP presents this MLK luncheon that offers food, community spirit, and inspiring history lessons. Admission is $7.88.

Where: ECMN Building, 1101 West Broadway Ave., Minneapolis

More info: https://bit.ly/408gzxZ

ShelettaMakesMeLaugh.com presents an MLK Day of Service for Black women

When: January 20 · 12-1 p.m.

What: To honor Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s legacy with a day of service, podcaster, comedian, and radio host Sheletta Brudidge is inviting Black women to meet her at Tubman Center, a shelter for survivors of domestic abuse, to drop off new and unused bedding and pillows.

Where: Tubman: Harriet Tubman Center East, 1725 Monastery Way, St. Paul

More info: bit.ly/ShelettaMLKDayofService

MLK Living the Dream Celebration

When: January 20 · 6-9 p.m.

What: As part of the Minneapolis Parks and Recreation Board’s series of MLK events, this annual gathering offers speakers, live entertainment, and the presentation of the Living the Dream Award. Check the website for unfolding details. This is a free event.

Where: Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Rec. Center, 4055 Nicollet Ave. S, Minneapolis

More info: https://bit.ly/3C0iiNE

Exploring Creative Actions for Justice

When: January 23 · 9 a.m. – 12 p.m.

What: Honor the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. by listening to a distinguished panel of civic leaders and change agents discuss, unpack, and apply King’s ideas on creative protest. Panelists will engage students, faculty, and staff around the legacy and relevance of MLK in the context of 21st-century America and their own respective work environments/spheres of influence. The event includes breakfast, a performance by a youth choir, a roundtable dialogue with scholars and activists, a blanket-making service project, and more.

Where: Minneapolis College, 1501 Hennepin Ave., Minneapolis (Room T.1400)

More info: minneapolis.edu/mlk

Unity in Colors: A Martin Luther King Jr. Commemoration

When: January 24 · 1-3 p.m.

What: Join community members for this unique drop-in program that invites individuals of all ages and backgrounds to contribute to a collective masterpiece. Express your creativity through coloring pieces of art that will come together to form a stunning commemorative board dedicated to Dr. King’s vision of a harmonious and inclusive society. This is a free event.

Where: Sibley Park, 1900 40th St. East, Minneapolis

More info: https://bit.ly/4gNcmqk