Pillsbury United Communities has served the city of Minneapolis since 1879. For more than 140 years, our community builders have worked to power people, place, and prosperity. These are some of our stories.

The Golden Age: 1879 – 1917

1879 – 1917 | 1917 – 1940 | 1940 – 1960 | 1960 – 1980 | 1980 – present

Plymouth Congregational Church, 1905 (on right). Photo credit: Hennepin County Library

Our history dates back to 1879, when members of Plymouth Congregational Church began a Sunday School for the many newsboys of Minneapolis. From a cramped facility at the intersection of 2nd Street and Cedar Ave, their services continued to grow. The Bethel Mission, as it came to be known, soon expanded to offer the city’s first free kindergarten, as well as the first day nursery for the children of working mothers.

Bethel Settlement nursery, 1905. Photo credit: Minneapolis Tribune

In 1897, the efforts of early settlement houses like Chicago’s Hull House inspired leaders of Bethel Mission to reorganize as the Bethel Settlement. That same year, in North Minneapolis, members of the First Universalist Church and Church of the Redeemer founded Unity House at the intersection of 16th and Washington Ave N.

A typical settlement house residence at the turn of the century. Photo credit: Hennepin County Library

The settlement houses were organizations that worked for reform and uplift in the early 20th century. Settlement workers, typically drawn from the educated middle and upper classes, lived and worked in the settlement house. This gave them a first-hand glimpse at the social and economic conditions of some of the poorest neighborhoods in Minneapolis. Their approach was born of solidarity, not charity. A common sentiment expressed by settlement workers was this: “I am not my brother’s keeper. I am my brother’s brother.”

Pillsbury Settlement House. Photo credit: Hennepin County Library

By the early 1900’s, the needs of a growing city placed increasing pressure on the new settlement houses. In 1906, the Bethel Settlement established a new house in the Seven Corners neighborhood. Funded by a $40,000 donation from the Pillsbury family, they adopted a new name: Pillsbury House. They were joined by Wells Memorial House, which opened in the Harrison neighborhood of North Minneapolis in 1908; and by an expanded Unity House, which erected a new building in Near North in 1912.

The neighborhood room at Unity House. Photo credit: Hennepin County Library

Settlement houses offered a wide range of facilities and services to members of the community. Facilities common to most of the settlements included a gymnasium, a nursery, a nurses’ station, and a kitchen. In most cases, the gymnasium also doubled as an auditorium, banquet hall, and club room. Many of the facilities reflected the needs and desires of the immigrant communities they serve. At Wells Memorial, which served a neighborhood that was predominately Finnish, poor and working-class immigrants could experience the comforts of home in the settlement’s sauna.

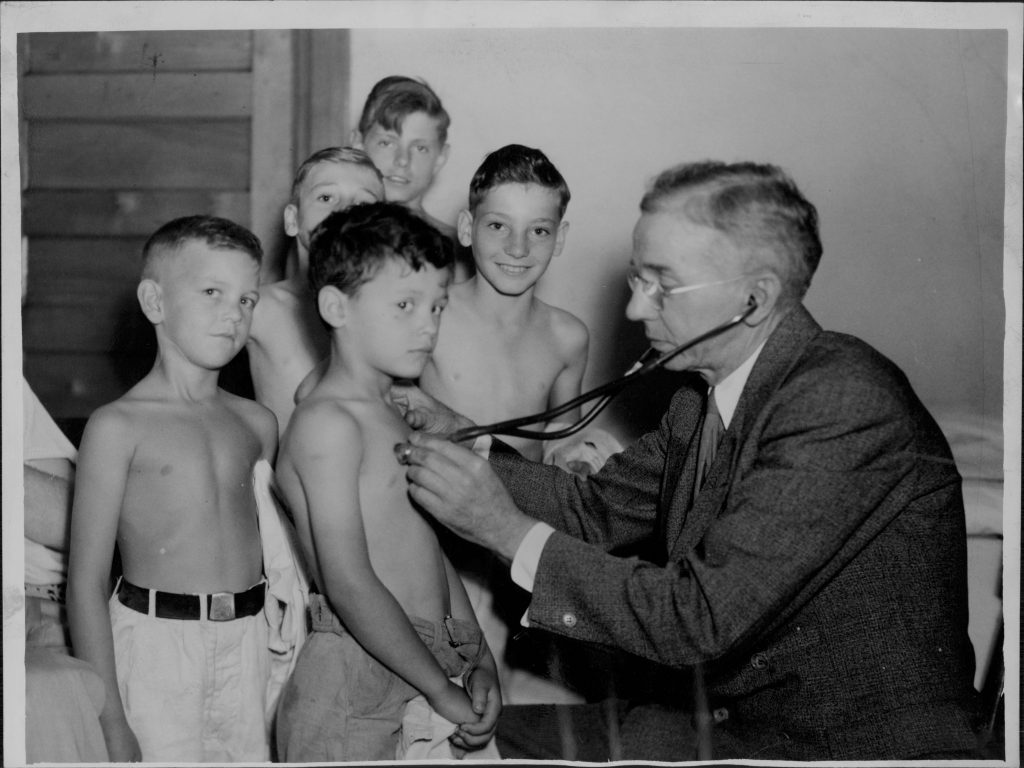

Kids at Wells Memorial receiving a physical examination from a visiting doctor. Photo credit: Hennepin County Library

Scientific advances in the early 20th century led to a newfound understanding of community health and sanitation, which hugely improved the conditions of our city’s poor and working-class communities. The settlements helped support these public health campaigns, including the struggle against infectious diseases like tuberculosis and polio. “Well Baby Clinics” helped connect new mothers with knowledge and resources to ensure the health and safety of their infants.

Women meeting at Elliot Park Neighborhood House. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

It’s no coincidence that women represented many of the early settlement house workers and leaders. Among the growing cohort of middle-class women with college educations, settlement work provided an alternative to marriage—and an opportunity to participate in civic life at a time before they could legally vote. For some, their time at the settlement was a brief interlude; for others, it became a lifelong commitment.

“Fresh air activities” for Pillsbury House youth in the late 1910s. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

Outdoor camping and “fresh air” activities were an early development of the settlements, offering relief from urban working-class neighborhoods that many city leaders believed to be unhealthy for children. Every summer, settlement workers would shuttle dozens of young people to far-flung locations like Minnetonka and Waconia for a few weeks of fishing, swimming, and other outdoor pastimes.

Elliot Park Neighborhood House seniors dressed up for a performance. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

The performing arts were another key focus of the early settlements. At Pillsbury House, monthly Peter Pan Nights featured songs, dances, and skits performed by community members of all ages. Pillsbury House board member W. Scott Woodworth (a “well known Minneapolis grain man” and arts supporter) directed the mixed chorus at the house and began a long-running concert series that continued well after his death in 1929.

A child on the see-saw at Pillsbury House, date unknown. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

The settlements played a major role in the “playground movement” of the early 20th century. Few public playgrounds were available in Minneapolis at the turn of the century. By 1915, most of the settlement houses had built outdoor spaces for neighborhood children to play—and they were some of the first to be made available to the public.

“The Settlement has stood first of all for understanding and sympathy between people sprung from different races and living under different conditions. … In short for fulfilling the command, ‘To love thy neighbor as thyself.'”

–Mary Thayer Hale, founding board member, Pillsbury Settlement House

The Great War and Great Depression: 1917 – 1940

1879 – 1917 | 1917 – 1940 | 1940 – 1960 | 1960 – 1980 | 1980 – present

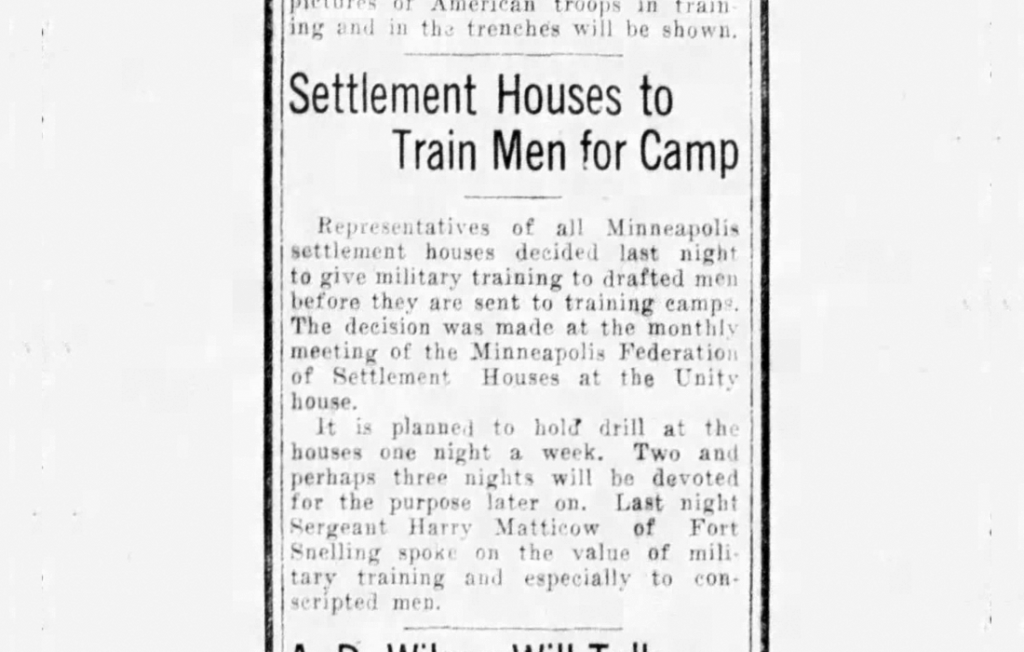

Credit: Minneapolis Tribune

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, the settlement houses played a key role in the war effort. Settlements hosted draft boards and offered up their clubrooms and athletic facilities for training exercises. The settlements also organized dances and other entertainment for soldiers training at nearby Fort Snelling.

Credit: Minneapolis Tribune

For those who hadn’t shipped out, war rationing led to shortages of food, clothing, and other basic necessities. The overseas deployment of many fathers, sons, and brothers created new hardships for many families in Minneapolis. In these areas and more, the settlement houses worked to support the war effort at home.

An advertisement for the 1919 War Chest, benefitting the settlement houses of Minneapolis. Credit: Minneapolis Tribune

Yet perhaps the greatest impact of World War I was the emergence of federated funding. Amid dwindling donations and volunteer shortages as a result of the war effort, local business leaders organized the War Chest fundraising campaign in 1918 to support local welfare work. They partnered with the Council of Social Agencies, of which many of the settlements were founding members, to select appropriately worthy causes.

Credit: Minneapolis Tribune

The War Chest campaign formed the precursor for the present-day United Way. A new influx of funds allowed the settlement houses to expand their activities, but it also reduced their independence and subjected them to new oversight by representatives of the Minneapolis business elite. By the 1920’s, the Community Chest (as it came to be known) was the primary funding mechanism for settlements in Minneapolis and many other major cities.

Credit: Minneapolis Tribune

Although the end of World War I brought some temporary relief, the settlement houses soon found themselves responding to the new challenges of the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic. At Pillsbury House, staff quickly opened a soup kitchen to provide nourishing food for families affected by the flu. In partnership with local Boy Scout troops, Pillsbury House delivered more than 350 quarts of soup every week to families in need.

Settlement house children being “Americanized.” Photo credit: Minnesota Historical Society

By the end of World War I, changing immigration policies had slowed the arrival of newcomers to Minneapolis. Civic leaders doubled-down on the importance of “Americanizing” immigrant communities, and the settlement houses were a key venue for these activities. Classes in basic civics helped introduce many “new Americans” to the tenets of American citizenship.

A young participant in Americanization activities at Pillsbury House. Photo credit: Minnesota Historical Society

However, the project of Americanization also contributed to new currents of nativist and white supremacist thought that emerged in the 1920’s, including a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan in Minneapolis. Alongside the emergence of restrictive housing covenants in 1919, these activities contributed to a state of de facto segregation at the settlements that continued well into the 1940’s.

The mailbox at newly opened Camp Manakiki. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

Following the continuing success of the settlement houses’ summer camping programs, the 1920’s saw many of the settlements purchasing land for dedicated camping sites. In 1921, Pillsbury House secured four acres on the shores of Lake Waconia and named it Camp Manakiki, after the grove of maple trees that grew on the land.

Exterior of Elliot Park Neighborhood House located at 22nd and Park. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

In 1930, Washington Neighborhood House was renamed Elliot Park Neighborhood House in honor of its home on the east side of downtown Minneapolis. They soon outgrew their original location and moved to a new house in the Phillips community, at the intersection of 22nd Street and Park Avenue.

Washington Neighborhood House basketball team. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

The shortage of able-bodied young men that resulted from the Great War had a huge impact on organized athletics, and new amateur athletics leagues emerged in Minneapolis to fill the gap. After the war, individual and team sports for children and young adults became a more significant focus of the settlement houses’ work.

Settlement house kittenball champions posing with trophy. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

The 1920’s saw the emergence of “kittenball,” also known as “diamondball,” and Minneapolis was one of the first cities where the sport was played. Many settlement houses fielded teams of young women to take part in this new sport, which is better known today as softball.

The Pillsbury House gym decorated for the All-Nations Basketball Tournament. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

At Pillsbury House, head resident Ed Currie organized the All-Nations Basketball Tournament after overhearing a playground argument between two boys. Each team represented the native country of its players, with teams like the Irish and the Norwegians battling on the court to settle the age-old question of which nation fielded the best basketball players.

“The settlement house must be a neighborhood club to those whom it serves. We must be literally father and mother, brother and sister, playmate and chum, advisor and nurse to the thousands to whom we open our doors.”

— Margaret Chapman, head resident, Wells Memorial Settlement House

War and Peace: 1940 – 1960

1879 – 1917 | 1917 – 1940 | 1940 – 1960 | 1960 – 1980 | 1980 – present

Credit: Minneapolis Tribune

When the U.S. entered World War II in December 1941, the settlements were ready to step up. Representatives of the armed services and the local draft boards were routinely hosted at the settlements to assist young men who were eligible to enlist. Civilian defense boards also operated out of many of the settlements.

Credit: Minneapolis Tribune

As with the First World War, the settlements worked to support the domestic war effort as well. Child care centers at the settlements allowed more women to enter the workforce as nurses, factory workers, and other key wartime positions. At Pillsbury House, a plaque in the foyer commemorated top donors to the regular Red Cross blood drives hosted on-site.

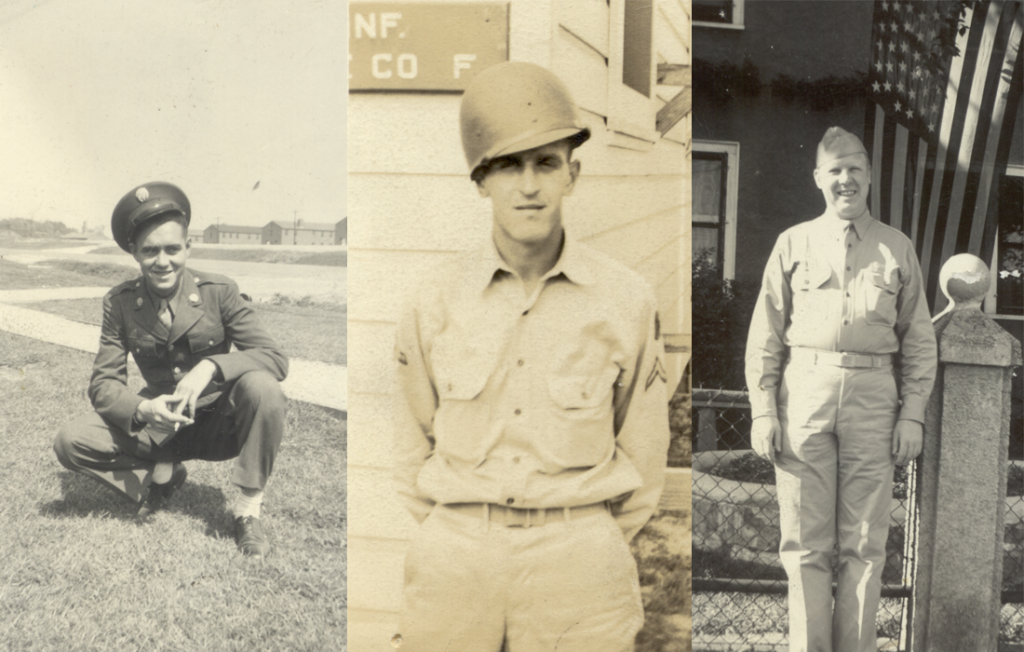

Pillsbury House community members who served in the armed services. Photo credits: University of Minnesota SWHA

Under the leadership of Ed Currie, Pillsbury House kept in close contact with its enlisted boys. Every week, kids at Pill House prepared a newsletter, the Scandal Monger, which they mailed to community members in the armed forces. Many of the men sent back photos for safekeeping, of which a few examples are provided here.

Kids farming in the Victory Garden at Camp Manakiki. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

During wartime summers at Camp Manakiki, campers grew their own produce and raised cows, pigs, and chickens in the camp’s victory garden. All campers were weighed at the start and end of the summer; even at the height of wartime rationing, a young camper could gain ten pounds after a couple of weeks at camp.

Junior competitors at the Golden Glove boxing tournament. Photo credit: Hennepin County Library

Youth athletics became an increasingly large part of the settlement house program during the ’40s and ’50s, and youth boxing was uniquely popular among the children and families of Minneapolis. (When we say “youth,” we really mean it! Most of these kids got their start as young as eight or nine years old.) Many of the era’s prominent local boxers got their start at Unity House and Pillsbury House, and the settlements regularly fielded top competitors at the city-wide Golden Glove tournament.

Emanuel Cohen Center, established in North Minneapolis to serve a predominately Jewish community. Photo credit: Hennepin County Library

Until the 1940’s, the communities of North Minneapolis were composed of immigrants who were predominately Eastern European and Jewish. As the ’40s continued, these residents found themselves living alongside an increasing number of African-American neighbors who had arrived from Chicago, Detroit, and other northern industrial cities.

Community members meeting in a Northside settlement house. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

Federal programs such as the G.I. Bill made it possible for many war veterans to pursue higher education and home ownership—opportunities that were not always made available to veterans of color. This new reality, occurring alongside the broader dynamics of white flight in changing urban neighborhoods, led many long-time Northsiders to relocate to nearby suburbs like Golden Valley and St. Louis Park over the next several decades.

Teens at the Elliot Park Neighborhood House canteen. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

Another social transformation occurring in the years after WWII was the emergence of the “teen-aged” demographic, leading to widespread concerns over the issue of “juvenile delinquency.” Inspired by the USO programs shown in the papers and newsreels, canteens at Elliot Park and Unity House provided safe recreational spaces for this newly empowered cohort of young people. Across town at Pillsbury House, a committee of teenagers began to organize Saturday night dances that drew more than 300 attendees per week.

Children in the Elliot Park Neighborhood House program for developmentally disabled youth. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

By the mid-’50s, Elliot Park Neighborhood House was a citywide leader in providing day care for young children with developmental disabilities. The success of their work, and an ever-growing waiting list, spurred a statewide expansion of funding for programs serving young people with disabilities.

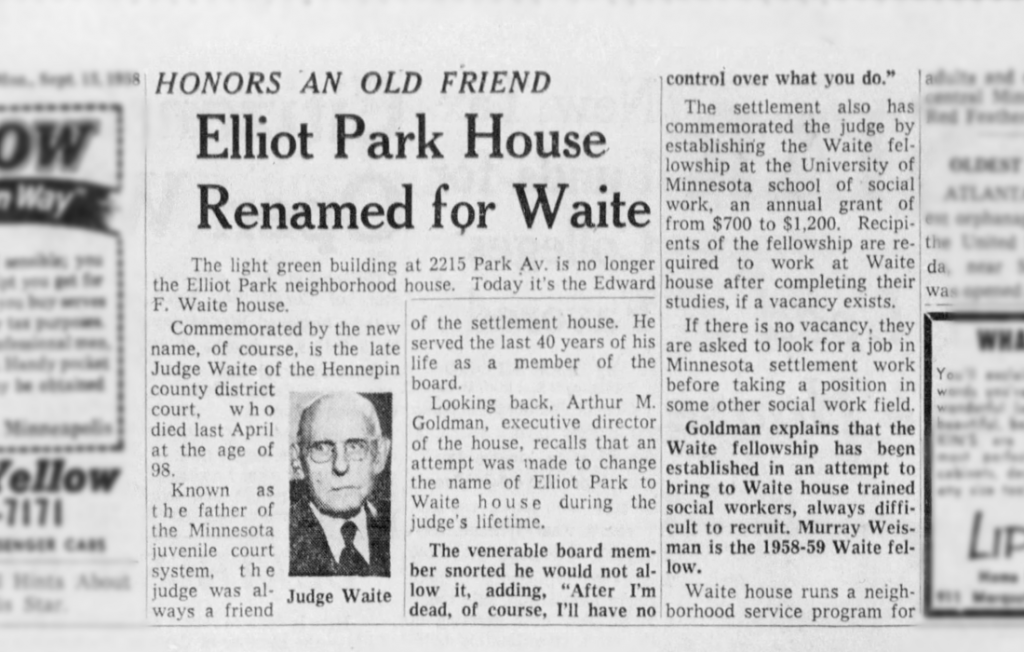

Credit: Minneapolis Star

1958 saw the death of Judge Edward F. Waite, a local advocate for children’s causes who was also a founding board member of Elliot Park Neighborhood House. In his honor, the leadership at Elliot Park voted to rename the house in his honor: E.F. Waite Neighborhood House—or Waite House for short.

Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

In February 1959, Pillsbury House merged with the Citizens Club, which was based out of the neighboring Seward community. As staff at the newly renamed Pillsbury Citizens Service began integrating their operations across a widened service area, they could not have expected that the biggest changes were yet to come in the tumultuous ’60s.

“When something succeeds after previous failures and you see a worthwhile product and can think, ‘Yup, I helped to mold that’—that’s a feeling money can’t buy and no one can take away from you.”

— Ed Currie, head resident, Pillsbury Settlement House

A City Transformed: 1960 – 1980

1879 – 1917 | 1917 – 1940 | 1940 – 1960 | 1960 – 1980 | 1980 – present

Pillsbury House undergoing demolition in April 1968. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

The ’60s were a time of radical transformation within Cedar Riverside, including the expansion of the University of Minnesota’s West Bank campus, the early stages of development for Riverside Plaza, and the construction of I-35W and I-94. Pillsbury House, located just east of the planned site of 35W, was slated for demolition—one of many buildings that fell victim to “urban renewal.” After a series of mysterious fires damaged the vacant building, Pillsbury House was torn down in April 1968. Today, the site is home to a parking ramp.

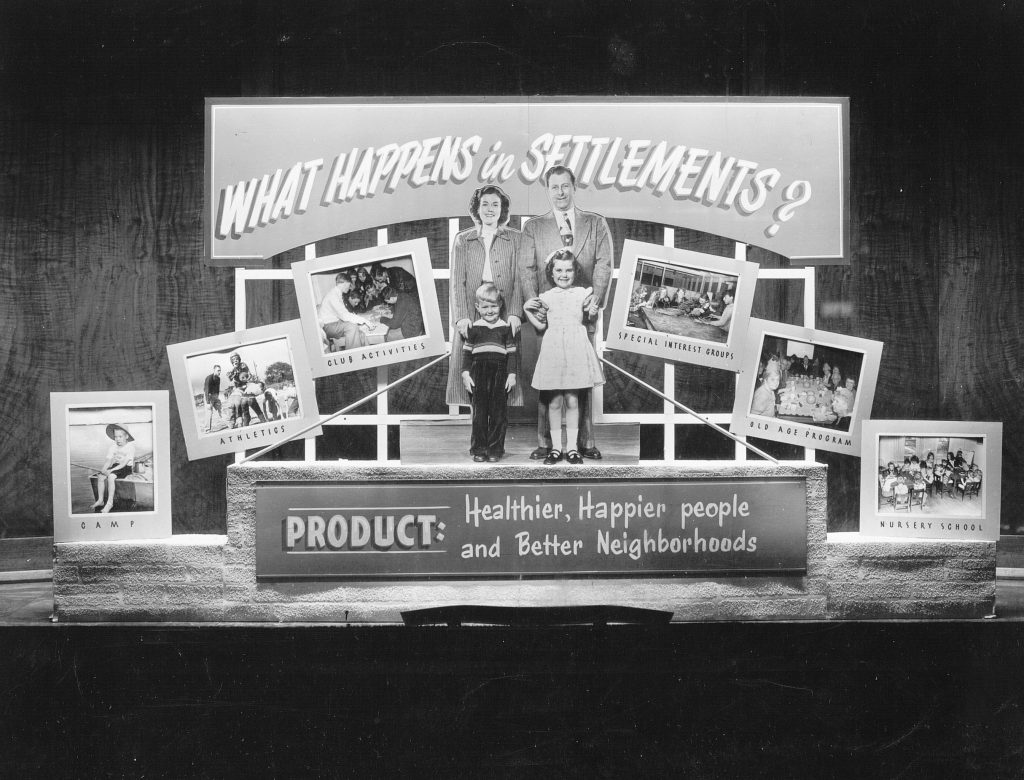

Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

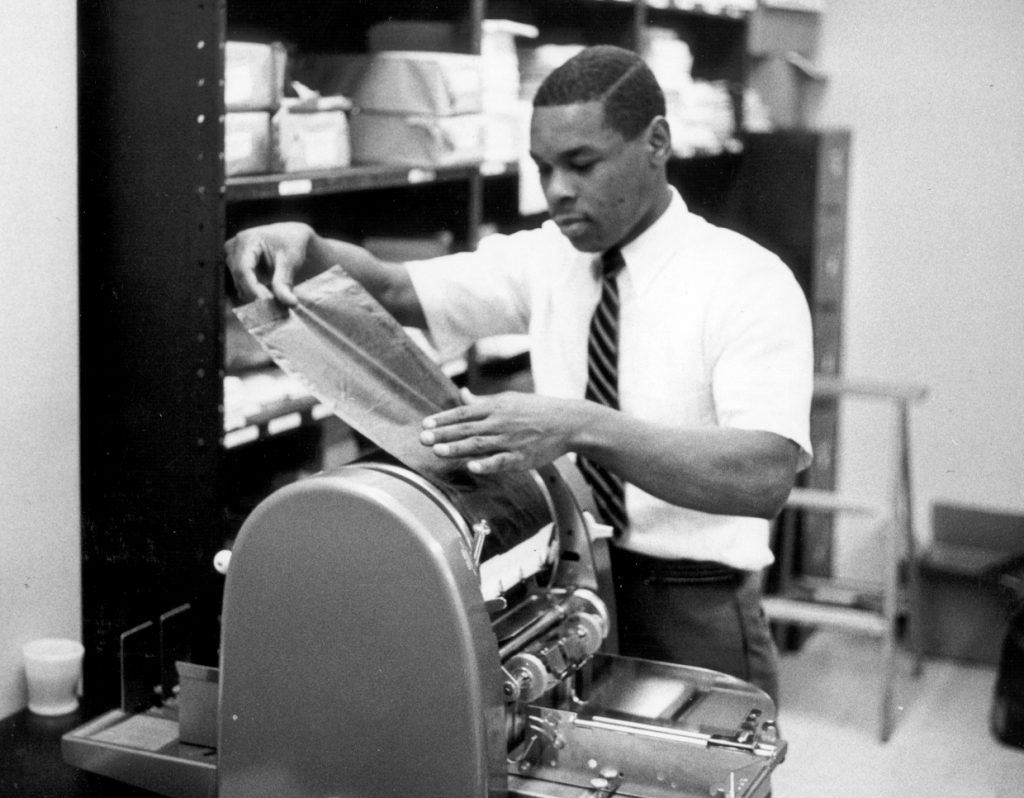

As the tensions of many of the city’s black residents began to boil over, the summers of 1966 and 1967 saw increasingly widespread public disturbances in North Minneapolis. The most prominent of these incidents, on Plymouth Avenue in the summer of 1967, drew wider attention to economic underinvestment and police brutality on the Northside. Believing that the unrest in North Minneapolis stemmed largely from a lack of economic opportunity, local settlement houses facilitated national workforce development programs like the Neighborhood Youth Corps in an effort to provide good jobs for young people on the margins.

Waite House community members. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

The ’60s were also a time of radical change for native and indigenous families in Minnesota. Federal termination policies spurred many native families to leave the reservation system for promised housing and employment opportunities in Minneapolis and elsewhere. The Phillips neighborhood formed the epicenter of this growing community, and Waite House introduced new programs and services to address the needs of their new neighbors.

Waite House youth protesting the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Minneapolis. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

Waite House staff supported local activists in protesting the Bureau of Indian Affairs and other public agencies that had failed to deliver on their promises to native communities. The American Indian Movement emerged out of this collective discontent, just down the street from Waite House. George Mitchell, a Waite House social worker, was among the founding members.

Wells Memorial, one of two settlements that merged to form Northside Settlement Services. Photo credit: Hennepin County Library

The late ’60s were a period of consolidation for settlement houses throughout the city. In North Minneapolis, Unity House merged with Wells Memorial to form North Side Settlement Services (NSSI) in 1967. The next year, Pillsbury Citizens Service merged with Waite House and formed Pillsbury-Waite Neighborhood Services.

Community meeting at a former settlement house in the early ’70s. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

These newly formed agencies understood their work more broadly—focusing not only on their immediate neighborhood surroundings, but on citywide programs and services. This was partly a result of the Johnson administration’s War on Poverty programs, which provided new funding opportunities while requiring more centralized record-keeping and program administration. By 1970, the classic “settlement house” was a thing of the past.

Credit: Minneapolis Star

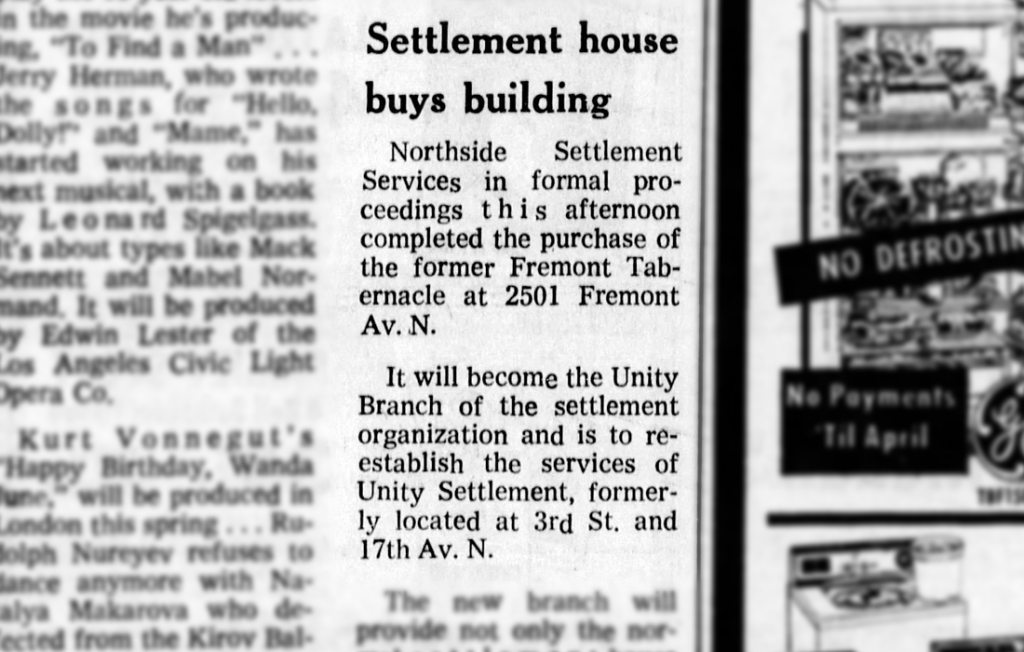

The ’60s and ’70s saw a number of new spaces added to the NSSI and Pillsbury-Waite networks. After the demolition of Unity House amid the construction of I-94, NSSI purchased the former Fremont Tabernacle to house the Unity Branch, a new headquarters and successor to the Unity House name. They also operated the Glenwood-Lyndale Center out of one of the Northside’s largest housing projects.

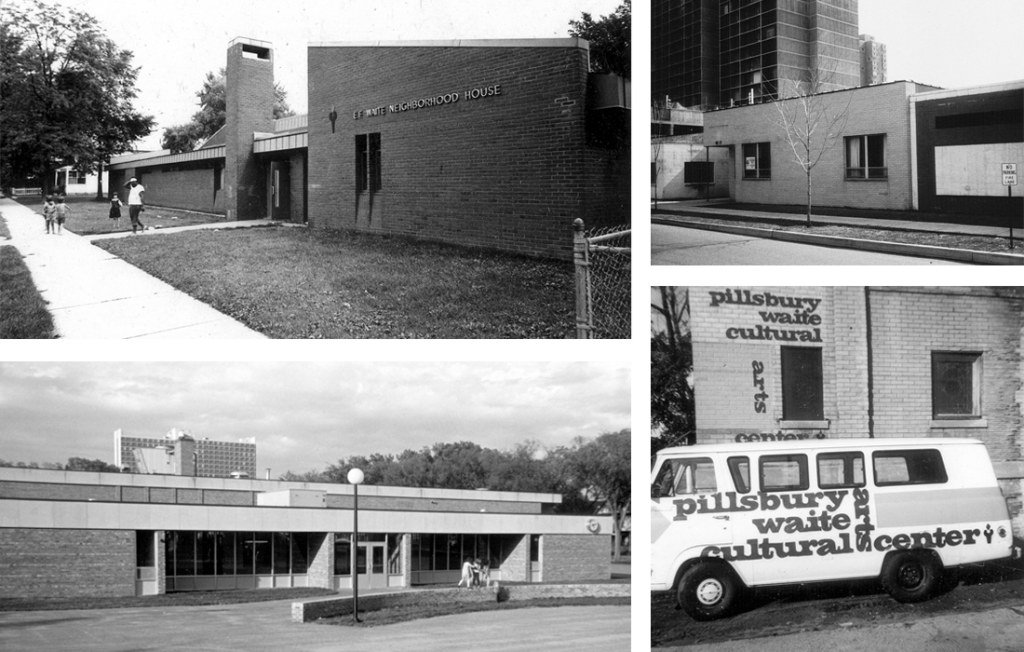

Pillsbury-Waite facilities in the ’70s (clockwise, from top left): Waite House, Currie Center, Cultural Arts Center, Matthews Center. Photo credits: University of Minnesota SWHA

Pillsbury-Waite also sought new spaces to fill the void left by the old Pillsbury House. The early ’70s saw Pillsbury-Waite partnering with the Minneapolis Parks Board to provide services in the newly opened Matthews Center in the Seward neighborhood. Many of our city’s foremost artists and playwrights found an early home at the Pillsbury-Waite Cultural Arts Center throughout the decade as well. And in 1978, Pillsbury-Waite returned to Cedar Riverside with the opening of the Currie Center in the shadow of Riverside Plaza.

Staff members at the Currie Center food shelf. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

By the mid-’70s, the backlash to Johnson-era welfare programs was already well underway. Cuts to federal nutrition programs created new pockets of food insecurity around the country, and the first food shelves opened to meet this growing need. In Minneapolis, Pillsbury-Waite first adopted this model at the Currie Center.

“We are in the midst of an unstoppable march toward development of new local social, political, and economic organizations that have the promise of transforming old, blinding patterns of organizational behavior; of healing the deep divisions in our society; and of creating new, more inclusive communities.”

— Tony Wagner, president, Pillsbury United Communities

Rebirth: 1980 – present

1879 – 1917 | 1917 – 1940 | 1940 – 1960 | 1960 – 1980 | 1980 – present

Supporters attending the opening reception of the new Pillsbury House. Photo credit: University of Minnesota SWHA

In 1979, the 100th anniversary of the Bethel Mission inspired the development of a new Pillsbury House, based out of the Powderhorn community in South Minneapolis. In a shift from the public-private financing model that had characterized the settlement houses in the ’60s and ’70s, the new Pill House was built entirely with private funds. Ground was broken in spring of 1980, and the building officially opened its doors in April 1981.

1982 saw NSSI acquiring a neighborhood center in Near North, on Oak Park Avenue. The building was erected in 1940 to house Emanuel Cohen Center, at a time when the neighborhood was still predominately Eastern European and Jewish. The Cohen Center left the Northside in the early ’60s for a new home in St. Louis Park, and the building passed between a number of owners until its acquisition by NSSI. New traditions like an annual Juneteenth celebration quickly took hold in the newly renamed Oak Park Center, reflecting the changing nature of North Minneapolis and its residents.

In 1984, Pillsbury-Waite Neighborhood Services merged with Northside Neighborhood Services (formerly NSSI). Anthony Wagner, NNSI president and himself a former Unity House “neighborhood kid,” was named president of the newly combined Pillsbury United Neighborhood Services.

Inspired by the work of Eugene Lang’s I Have a Dream Foundation, the FANS (Furthering Achievement through a Network of Support) program launched in 1989, providing tutoring and college scholarships to young people who were at risk of dropping out of high school. These FANS scholarships were funded by an annual ultramarathon race, which attracted long-distance runners from all over the world. The first cohort of FANS Scholars graduated high school in June 1996—and in 2019, FANS (and the FANS Race) celebrated its 30th year.

Photo credit: Fowsiya Husein

Minneapolis city council member Brian Coyle passed away from AIDS-related complications in 1991. As one of the first openly LGBT politicians nationwide, Coyle worked to ensure his constituents in Cedar Riverside had a strong voice throughout the redevelopment of their neighborhood. Brian Coyle Center, named in his honor, opened in Cedar Riverside in 1993. At the same time, immigrants from Somalia, Ethiopia, and Eritrea began arriving in Cedar Riverside, fleeing war and famine in their native countries. Coyle Center, located across the street from Riverside Plaza, quickly became a nexus for the city’s fast-growing East African diaspora community.

Continuing a long-running tradition, 2001 saw PUNS formally adopting a new name: Pillsbury United Communities. As of 2020, this is the last time our agency has changed its name.

Waite House staff Jeremy Hernandez and Kim Dahl, recognized for their heroism in rescuing youth from the I-35W bridge collapse. Photo credit: David Joles, Star Tribune

In August 2007, a catastrophic structural failure led to the collapse of the I-35W bridge during rush hour traffic. 63 children on the Waite House bus were returning from a field trip when the bridge collapsed. Images of the bus, which came to rest near a burning semi-trailer truck, were widely circulated in national media. Although members of the youth program staff suffered injuries in the fall, all of the children on the bus escaped with only minor injuries. In 2009, 22-year-old Waite House staff member Jeremy Hernandez received a civilian Medal of Honor for leading the children to safety after the crash.

Throughout the ’90s and ’00s, Pillsbury United began exploring new models to ensure the financial sustainability of its work. The social enterprise model provided a new platform for the agency’s mission. Full Cycle Bike Shop opened its doors in 2008. 2016 saw the launch of Sisterhood Boutique and the purchase of North News. And in 2017, KRSM Radio took to the airwaves while North Market opened for business. (Click here to learn more about our social enterprises.)